Thyroid and iodine are highly interconnected as iodine is an essential part of the thyroid hormones, T4 and T3.

Almost 75% of iodine in the body is used by the thyroid.

Because our body does not produce iodine, insufficient iodine results in an insufficient hormone production.

When the body’s tissues do not receive the required thyroid hormones symptoms of hypothyroidism start to appear.

In contrast, when an overcompensation of iodine occurs, this inadequate response results in hyperthyroidism.

Order an At-Home Thyroid Test.

Normal TSH levels – how TSH values change with age.

Thyroid and Pregnancy – how thyroid impacts pregnancy.

Role of Iodine in Healthy Thyroid – how iodine balances thyroid hormones.

At Home Thyroid Test – a test that measures TSH, free T4, free T3, and TPO.

Tips for Understanding Thyroid Test Results – ranges for TSH, free T4, free T3, and TPO.

Food Sensitivities to Worry About – Allergy, Intolerance, and Celiac Disease.

Iodine was first discovered in 1811 and was soon implicated in thyroid problems.

The thyroid hormones work through very specific receptors in the cells.

They selectively regulate how certain genes express themselves in key tissues and organs, e.g., in liver, pituitary gland, muscles, and development of a child’s brain.

Insufficient supply of iodine results in an insufficient production of thyroid hormones. This hormone deficiency starts to appear as visible health problems. A very well known example is goiter, an enlarged thyroid gland with swollen appearance of the neck.

Other well known conditions include hypothyroidism, mental retardation in newborns, reproductive impairment, and a decreased rate of child survival during pregnancy.

To counteract low hormone levels, the thyroid enlarges to produce more. If the iodine deficiency is mild, this may be enough to maintain healthy levels.

The thyroid stays visibly large with potential risks of neck compression. Eventually, this may cause hyper-functioning autonomous nodules that can cause hyperthyroidism in future.

If the thyroid can’t produce enough hormone, it results into hypothyroidism with its well known symptoms.

In general, Iodine-deficiency-syndrome has several symptoms. According to CDC, these include:

goiter

cretinism

intellectual impairment

brain damage

mental retardation

stillbirth

congenital deformities

increase in perinatal mortality

How much iodine one consumes also influences the type and incidence of thyroid cancer.

Regions that no longer have their historically well-known iodine deficiency anymore (e.g. in Argentina and Austria), the rate of papillary thyroid cancer increased. However, follicular cancer has subsequently decreased (Harach 1985).

Research suggests iodine may have effects independent of the thyroid. For example, studies indicate (Ghent 1993) that fibro-cystic breast disease is very sensitive to iodine nutrition. It improves with iodine supplementation. (as unbound I2 molecule rather than iodide complex).

Although not so prevalent in developed countries, goiter is the most visible sign of iodine deficiency. It is the first step in a series of events that follow during iodine deficiency.

Hypothyroidism—which is a lack of adequate production of thyroid hormones, primarily from iodine deficiency—can result in several health conditions.

The symptoms of hypothyroidism include:

fatigue

lethargy

cold intolerance

slowed speech and intellectual function

slow reflexes

hair loss

dry skin

weight gain

constipation

Hyperthyroidism is a opposite condition with excessive production of thyroid hormones. The symptoms of hyperthyroidism include:

nervousness

anxiety

heart palpitations

rapid pulse

fatigability

tremor

muscle weakness

weight loss with increased appetite

heat intolerance

frequent bowel movements

increased perspiration

often thyroid gland enlargement (goiter)

Almost one-third of the world’s population lives in areas that are iodine deficient and deal with these consequences. Although most of these people are in developing countries, many in the large industrialized countries of Europe are also affected.

In US, iodine deficiency receives little attention because it is widely assumed to be eliminated years ago.

Average iodine levels in different age groups in US, plotted from the NHANES III survey:

About 90% iodine eventually excretes in the urine.

The urinary iodine values directly reflect dietary iodine intake. Therefore, urinary iodine (or UI) analysis is the most common method for assessing iodine status for public health. It’s a quick and accurate method to quantify iodine content in population.

Based on large data from the general U.S. population (in 2005-2006 and 2007–2008), the median urinary iodine concentrations were 164 um (microgram per liter). The range for this data was 154 to 173 ug/L with 95% confidence intervals or 2-standard deviations (Caldwell 2011).

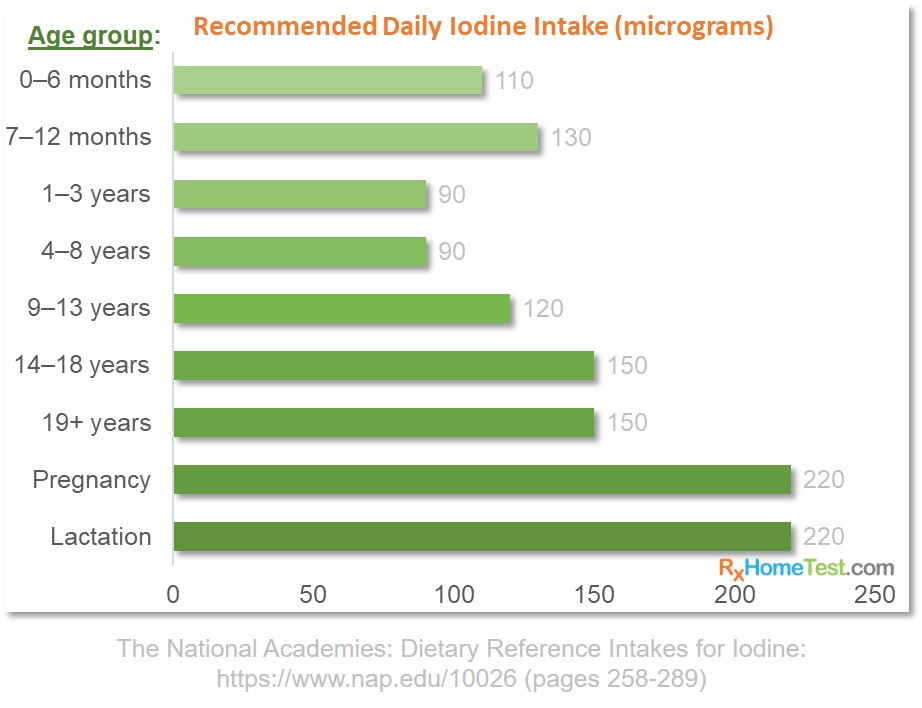

Dietary values recommended for Iodine (based on the Dietary Reference values from the National Academies Publications):

Several organizations and governing bodies regularly make iodine recommendations. These include International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (ICCIDD), the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and the Food and Nutrition Board of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

In summary, the recommendation for daily amount are (Dunn 1998):

Adults: 150 ug/day for adults.

Pregnant or women nursing infants: 200 ug/day.

Children: even lower amounts, about 90 – 130 ug/day.

Most people can consume large amounts of iodine without apparent problems (Braverman 1994), except those with preexisting iodine deficiency, autoimmune thyroid disease, and papillary cancer.

That’s because majority of this excess iodine excretes through urine without causing any problems. Intakes up to 1 mg iodine per day are safe for most people, and much higher amounts are usually tolerated without problem.

However, the upper limit for safe iodine intake is not well studied and can vary widely from person-to-person, and even by population. One group that may have problems with excess iodine is a community that has recent correction of iodine deficiency in a short period of time.

An iodine-induced hyperthyroidism is a predictable consequence of such a recent change (Stanbury 1998). The main victims of such a change are the elderly who have autonomous thyroid nodules. They are unable to regulate this newly available iodine properly. They also tend to produce excessive thyroid hormone . The problem further worsens due to poor monitoring of salt iodine concentration.

Without an adequate medical attention, delay in diagnosis and treatment compounds the problem.

About 50%-60% of the U.S. population uses iodized table salt today, a process that started in the late 1930s.

Globally, an estimated 70% of the world’s edible salt is iodized.

In recent years, highly publicized health campaigns in many developing countries, including India and China, have successfully lowered thyroid disorders, in particular during pregnancy.

Efforts to make salt iodization compulsory have not been very successful, and its use remains voluntary in many countries including United States. But salt iodization is mandatory in Canada despite sharing similar history of iodine deficiency as US.

In both Canada and US, salt is iodized with potassium iodide (KI). The necessary level is 100 ppm of KI, which amounts to approximately 77 microgram iodine/g of salt.

Most grocery stores stock both iodized and non-iodized salt side by side and sell at the same price. But consumers are only dimly aware of the difference.

Here is a list of foods that contain iodine (from NIH Office of Dietary Supplements).

Only a small percentage of salt in US comes from table salt.

Almost 70% of salt in diet comes from processed foods, which mostly use non-iodized salt (Dasgupta 2008). Americans obtain iodine from many sources although dairy and grain products remain the primary sources of iodine in the American diet (Murray 2008).

Iodine supplements improve the health and productivity of domestic animals—for the same reasons it benefits people—it is a common ingredient of animal feeds. Therefore, dairy products, eggs, and meat frequently contain high levels of iodine depending on the content in animal feeds. However, none are monitored as part of the American diet.

About 60 year ago, baking industry started using iodate as a bread stabilizer. It significantly increased the iodine intake of the American population. However, this practice has recently declined.

A common food coloring called erythrosine contains large amounts of iodine. Most of it may not be bioavailable—unusable by the body—but it appears in most analyses of urinary iodine affecting the results.

Many multivitamin supplements contain up to 150 ug of iodine per tablet.

Some people consume extra iodine from kelp or other so-called health foods. Most of these are unrecognized and none are regulated, except for iodized salt. Also, changes in iodine content of these products usually occur without any public notification or awareness.

Iodine is also widely available as a radiocontrast medium, in medicines such as amiodarone and topical antiseptics, and for water purification.

The damage is significant when iodine deficiency causes hypothyroidism during pregnancy or early life in children. That’s because thyroid hormone is essential for proper development of the central nervous system, particularly its myelination (process of neuron sheath formation).

The under-development of children due to iodine deficiency was called 'cretinism' where the growth is stunted to barely a meter with severe goiter and other symptoms. The Swiss had a long history of iodine deficiency and often whole towns had visible goiters. The last ice-age depleted the soil of Alps from iodine causing wide-spread health problems until 1920s when iodized salt finally solved the problem.

The fetus relies upon maternal iodine for thyroid hormone synthesis until week 18. Therefore, the health risk from mother’s iodine deficiency to a baby is highest during first trimester.

Research shows a mother’s urinary iodine concentration of 50 microgram per liter or less during the first half of pregnancy can cause thyroid problems such as enlarged thyroid gland and high TSH and thyroglobulin concentrations in the newborn (Glinoer 1995; Pedersen 1993).

Children with mothers who were hypothyroid at this critical period frequently show permanent mental retardation. It is not possible to correct this damage later using iodine or thyroid hormone.

Iodine deficiency also threatens child survival. Several studies show that when deficiency is corrected neo-natal mortality may reduce 50% or more (DeLong 1997). Supplementing iodine during pregnancy can reduce the risk of post-partum goiter due to iodine deficiency during pregnancy and lactation (Glinoer 1992; Antonangeli 2002).

Research shows iodine supplementation before pregnancy, in comparison with iodine supplementation during pregnancy, appears to reduce the risk of for abnormal thyroid function that results in low free T4 and elevated TSH (Moleti 2008).

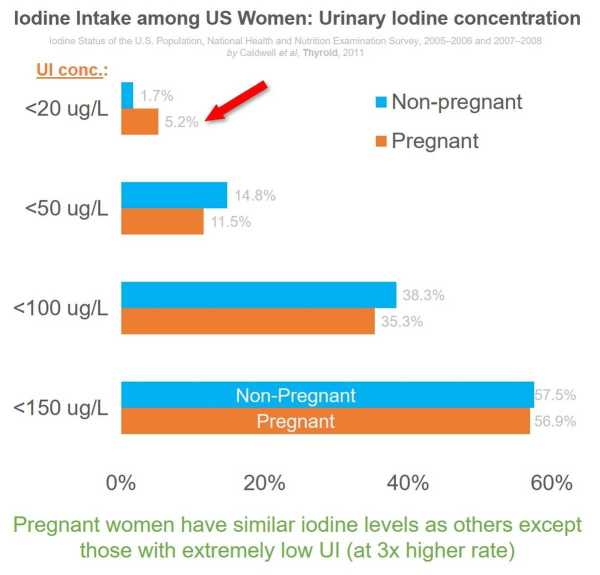

In US, data for women of childbearing age (approximately 14 – 49 years) show the median urinary iodine concentration to be around 130 microgram/liter.

The increase in awareness of thyroid impact on pregnancy in general is helping women maintain healthy levels. However, the prevalence of a UI concentration below 50ug/L remains around 15%.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (for 2005-2006 and 2007-2008) show that except for extremely low UI concentrations, overall iodine levels among pregnant women are comparable to non-pregnant women.

For pregnant women, the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine recommends an iodine intake of 220 micro-gram (per-person-per-day; based on data from US Institute of Medicine Panel on Micronutrients DRI: dietary reference intakes 2001). This dietary dose is approximately equivalent of a UI concentration of 150ug/L.

Almost all women of childbearing age with potentially low iodine intake can benefit from iodine supplementation. That’s because they may be unaware that they are in the early stages of pregnancy—a time when iodine sufficiency is extremely important.

The risk of thyroid related problems in newborns can be proactively reduced by avoiding maternal thyroid issues due to iodine deficiency (Becker 2006).

More than half of pregnant women have below the desired iodine levels, as shown in the data below for urinary iodine.

Urinary iodine concentration is common method to test iodine levels in large population. However, individuals should check their thyroid hormone deficiency using a thyroid blood test.

The key markers to monitor is TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone). However, normal TSH levels may not necessarily mean a healthy thyroid.

Checking the T4 (thyroxine) and T3 levels gives a full picture of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Thyroid axis. Additionally, checking for the presence of TPO anti-bodies–for potential threat to the thyroid from auto-immune diseases also helps.

Because thyroid hormone levels fluctuate significantly during pregnancy, regular urinary and blood sample checkup in childbearing women is very useful. As the baby relies on mother’s thyroid levels, checking free T4 during pregnancy ensure healthy child development and normal pregnancy.

Elderly population is at higher risk of thyroid disorders and needs regular monitoring.

Under Medicare coverage, a patient may test for thyroid dysfunction if their doctor recognizes a broad range of symptoms associated with thyroid dysfunction. The National Academy of Medicine recognizes treatment will benefit patients who present with significant symptoms or complications.

Those with history of a thyroid disease or exposure to known thyrotoxic chemicals are covered by Medicare. Testing is crucial because thyroid dysfunction is a known cause or an aggravating factor for many conditions such as atrial fibrillation, diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia.

Once tested, available treatments can improve biochemical and physiological symptoms of thyroid dysfunction. However, more research is necessary to understand how much treatment benefits in terms of improved survival, function, or quality of life.

What’s Happening to Our Iodine? by John T Dunn in J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998.

Iodine Status of the U.S. Population, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 by Caldwell et. al. in Thyroid, 2011.

Thyroid follicles with acid mucins in man: A second kind of follicles? by Harach in Cell and Tissue Research, 1985.

Iodine replacement in fibrocystic disease of the breast by Ghent, Eskin, & Low in Canadian Journal of Surgery, 1993.

Iodine and the Thyroid: 33 Years of Study by Braverman in Thyroid, 1994.

Iodine-Induced Hyperthyroidism: Occurrence and Epidemiology by Stanbury et. al. in Thyroid, 2009.

Iodine Nutrition: Iodine Content of Iodized Salt in the United States by Dasgupta, Liu & Dyke in Environ. Sci. Technol., 2008.

US Food and Drug Administration’s Total Diet Study: Dietary intake of perchlorate and iodine by Murray et. al. in J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol., 2008.

A randomized trial for the treatment of mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal effects by Glinoer et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1995.

Amelioration of some pregnancy-associated variations in thyroid function by iodine supplementation by Pedersen et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1993.

Effect on infant mortality of iodination of irrigation water in a severely iodine-deficient area of China by Delong et. al. in The Lancet, 1997.

Maternal and neonatal thyroid function at birth in an area of marginally low iodine intake by Glinoer et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 1992.

Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc by The National Academies, 2003.

CDC data on urinary iodine from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, published June 2018.

Medicare coverage of thyroid testing (National Academies).

Comparison of two different doses of iodide in the prevention of gestational goiter in marginal iodine deficiency: a longitudinal study by Antonangeli et. al. in European Journal of Endocrinology, 2002.

Iodine Prophylaxis Using Iodized Salt and Risk of Maternal Thyroid Failure in Conditions of Mild Iodine Deficiency by Moleti et. al. in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2008.

Iodine Supplementation for Pregnancy and Lactation—United States and Canada: Recommendations of the American Thyroid Association by Becker et. al. in Thyroid, 2006.