Celiac disease is an intolerance to gluten that damages the small intestine. Unfortunately, it's permanent but resolves when gluten is removed from the diet. There is no cure except to live with a gluten-free diet.

As the gluten comes into contact with inner lining of small intestine, it causes inflammation and damage to the absorptive surface. A compromised surface reduces fluid secretion, mal-absorption, and destruction of the intestinal lining.

A damage to the intestine causes lower absorption of fat and micro-nutrients, e.g., iron, folate (B9), and fat-soluble vitamins from the foods and they all end up in stool without any absorption. This can cause serious malnutrition.

Relatively immediate symptoms include abdomen pain, bloating, diarrhea, fatigue, and mouth sores. However, long term impact can be severe including weight loss, lower bone mineral density, iron and vitamin D deficiency, short stature and neurological disorders.

These symptoms may not always be as clearly visible and the inner lining may be completely damaged. However, the problem resolves when gluten is removed from diet and re-appears on re-introduction.

Order a Celiac Genetic Test kit.

Genetic Testing and Disease Inheritability – role of genetics on health.

The Differences Between Genetic and Antibody Celiac Tests - And which one to order.

Genetics of Celiac – short summary of the genes behind celiac.

A Brief History of Celiac – a short history of celiac.

A History of Gluten-Free Diet – a brief history of gluten-free diet.

Testosterone and Aging – research on the male hormone.

All About Vitamin D – review of symptoms and impact.

Celiac clusters around families, suggesting a strong genetic bias. Absence of certain genes can preclude any risk of celiac, however, not everyone testing positive may show the symptoms.

Experts (e.g. Mayo Clinic) recommend genetic screening of family members and relatives due to the high negative predictive value of testing–the disease is almost never likely to develop in those who are negative for both DQ2 and DQ8 gene markers.

Genetic susceptibility and consumption of gluten are two key requirements to develop gluten intolerance and celiac disease. Avoidance of gluten may be difficult, but the genetic susceptibility is easy to assess with an at-home celiac disease genetic test.

Testing for the IgA gluten anti-bodies is a first step in diagnosis of celiac disease. However, those with celiac tend to be deficient in IgA antibodies, requiring a biopsy of the intestine which makes the diagnosis complicated and tedious.

An IgG gluten sensitivity test is recommended as part of serologic screening for those deficient in IgA antibodies.

Celiac disease is a chronic disorder across the world, with about 1% of population affected in the western world. Despite the image of it being a western condition, celiac is common in North Africa, Middle East, China, north-western India and many parts of the world where wheat is staple food. The regional prevalence may also vary, e.g., 0.3% in Germany vs 2.4% in Finland.

Celiac is rare in Japan (with only 2 reported cases as of 2006), consistent with the rarity of associated DQ2 genes.

Experts believe only about 1 in 100 people are correctly diagnosed for multiple reasons. Symptoms may not always be clear, often overlap with other conditions, and require multiple steps for final diagnosis which may not be necessarily as clear as expected.

It may be difficult for some people to recognize that wheat, the main ingredient in their diet, can cause such a life threatening condition.

Diets vary across the globe, so does celiac. For example, rice is a staple diet southern India which has very limited celiac cases compared to northern India where wheat consumption is very common. Interestingly, the genes in both communities differ from those found in European population.

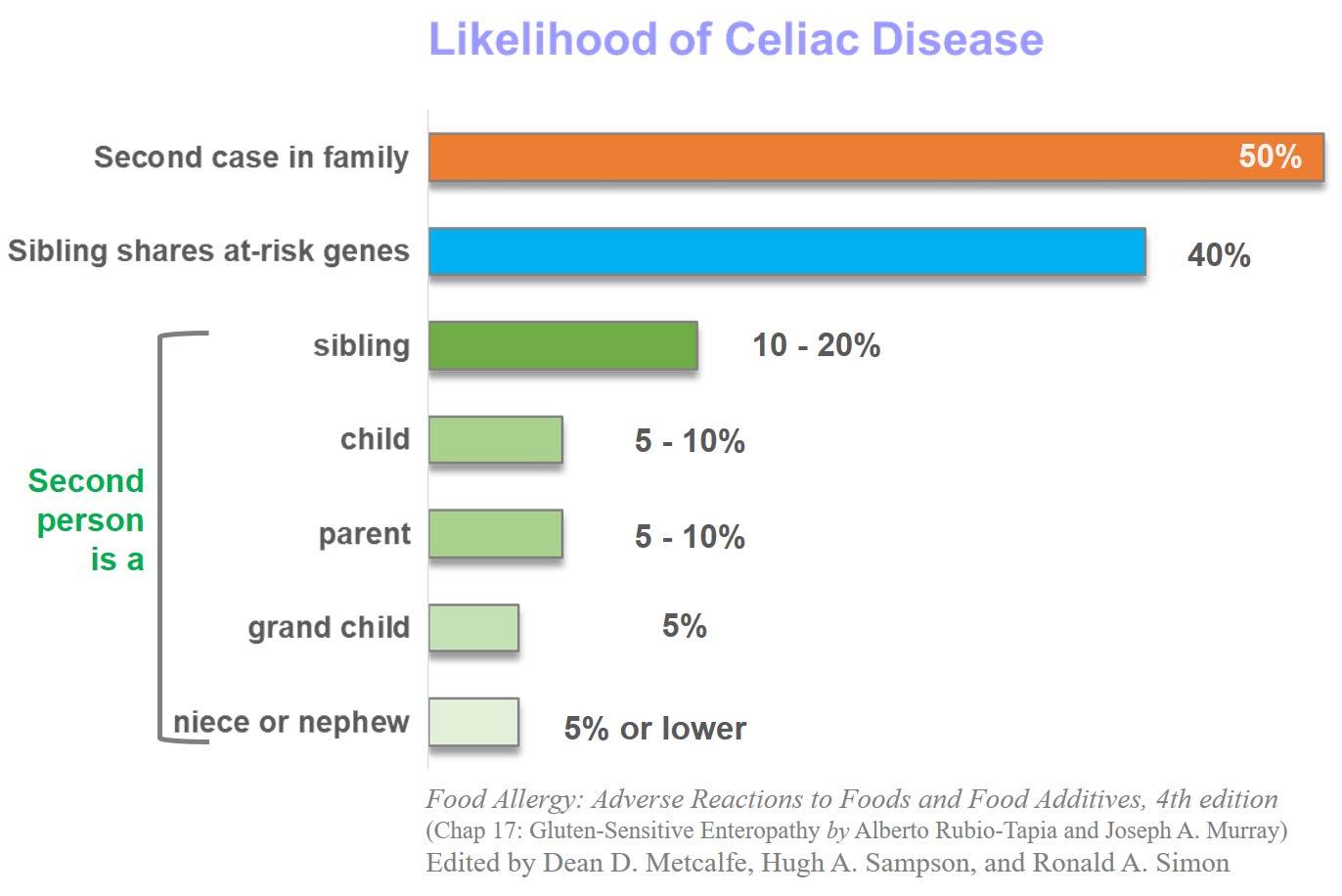

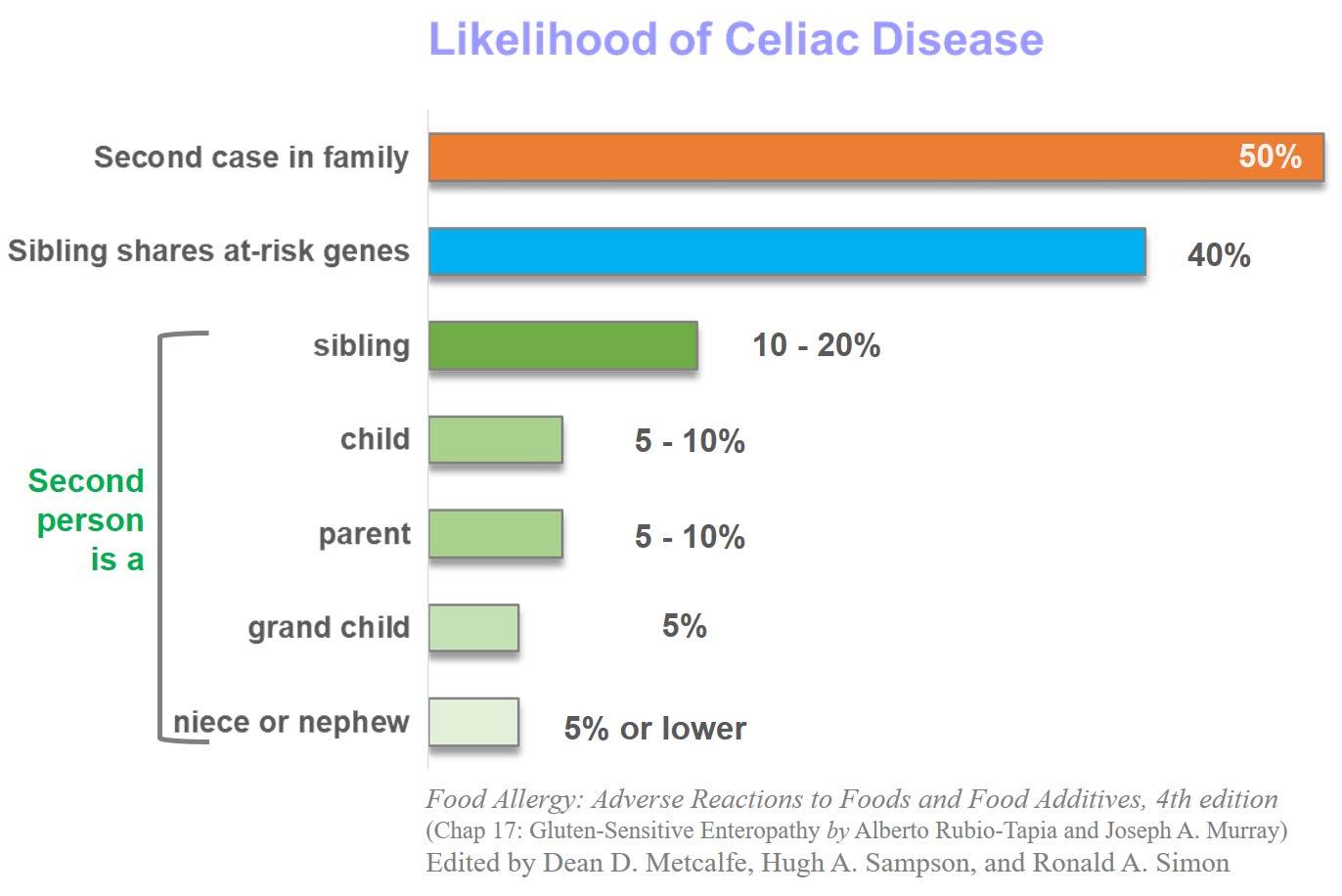

Because of a strong genetic component, relatives are disproportionately affected. The probability of a relative of someone with celiac disease testing positive is as high as 50%. Approximately 10-20% siblings and 5-10% parents or children also test positive. Siblings sharing same genetic markers have a likelihood of almost 40%.

Chances of celiac disease also rise for those who have relatives affected by Type 1 diabetes (3-16%), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (5%), or Down’s syndrome (5%).

There is a strong DNA signature to celiac disease suggesting genetic risk. In 90 percent cases, the affected person tests positive for a specific subset of HLA-DQ2 haplotype, DQA1*0501|DQB1*0201 (vs only about 30 percent in general population). Remaining 5 percent test positive for a subtype of HLA-DQ8. In almost all the remaining 5 percent, at least one of the two genes encoding of DQ2 (DQB1*0501 or DQA1*5010) is present.

Cells with these genes produce antigens that bind with the gluten enzyme. This triggers an immune response resulting in chronic inflammation and damage to the intestinal lining that is responsible for nutrient absorption.

The DQ2 and DQ8 gene haplotypes are necessary but not a sufficient condition for celiac disease. So far, at least 39 non-HLA genes have been identified for the celiac predisposition.

Few key steps in the evolution of disease are: presence of gluten in diet as a trigger, changes in the intestinal lining on exposure, an enzyme break down of gluten, genetic predisposition, and immune response to the enzyme affected by gluten resulting in inflammation and other symptoms.

Symptoms change frequently and are systemic in nature affecting the whole body. These include:

Weight loss

Bloating (abdominal distention – or expansion) in almost half of the people

Chronic fatigue

Iron deficiency (sometimes with anemia) due to improper absorption of nutrients

Recurring abdomen pain

Reduced bone mineral density

Canker sores (aphthous stomatitis) – benign and non-infectious mouth sores

Short stature

High levels of amino-transferase enzymes

Untreated celiac disease can results in complications including

Osteoporosis

Reduced spleen function

Infertility or frequent miscarriages

Neurological disorders

Ulcers in the intestine

A 2012 study by the New England Journal of Medicine says, “testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may be useful in at-risk persons (e.g., family members of a patient with celiac disease)”. Such testing has a “high-negative predictive value, which means that the disease is very unlikely to develop in persons who are negative for both HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8”. In fact, “Up to 97% of cases”, the HLA phenotypes are prerequisite for celiac.

A 2019 Mayo Clinic study had similar conclusion calling for screening of family members.

Gluten has limited nutritional value and the sources (wheat, rye, barley) can be easily substituted. However, it helps absorb certain nutrients including fibers, iron, calcium, and folate.

Those avoiding gluten will have less absorption of these nutrients. Even very small amount of gluten is sufficient to cause problems since the lowest threshold for intestinal damage is 10-50 mg per day while a slice of bread has about 1500 mg of gluten.

Oats up to 70 g per day for adults and 25 g for children should have no effect on celiac patients. Oats do not have any gluten, but contamination during processing with other grains might make them unsuitable.

It may take between 6 to 24 months of gluten-free diet to return back to a healthy intestinal lining and normal anti-body levels.

Typically the IgA anti-bodies are annually checked for adherence and related conditions of osteoporosis and thyroid auto-immune disease are monitored.

There are significant differences in the origin and symptoms of the three conditions. Celiac is different because:

Symptoms can take weeks to years instead of hours for gluten sensitivity and minutes for wheat allergy

High restriction among those with DQ2 or DQ8 genes (in almost 97% cases) instead of only about 50% cases of gluten sensitivity and about 35-40% cases of wheat allergy.

Celiac disease patients will almost always have some levels of IgA antibodies but not in the other two.

Intestinal protein loss (enteropathy) almost always occurs in celiac but not in the other two cases.

Although all three conditions have similar symptoms, only celiac disease has higher chances of long term complications and co-existing conditions.

Celiac is an under-diagnosed condition and only the tip of the ‘celiac iceberg’ show clear symptoms. The recent westernization of diets across the globe and more awareness allows more people to identify their symptoms. However, a simple swab genetic test can check the genetic risk of celiac disease for those suspecting gluten intolerance even if their symptoms are difficult to observe.

Food Allergy: Adverse Reactions to Foods and Food Additives, 4th edition (Chap 17: Gluten-Sensitive Enteropathy by Alberto Rubio-Tapia and Joseph A. Murray). Edited by Dean D. Metcalfe, Hugh A. Sampson, and Ronald A. Simon.

Celiac Disease by Fasano et al in New England Journal of Medicine, 2012, vol 367, pages 2419-2426.

Mayo Clinic: Overview of celiac disease, last accessed Oct 2019.

Mayo Clinic study calls for screening of family members of celiac disease patients, last accessed Oct 2019.

The Celiac Disease Foundation, last accessed Oct 2019.

NIH: Genetic Home Reference for Celiac Disease and Genetic Risk, last accessed Oct 2019.